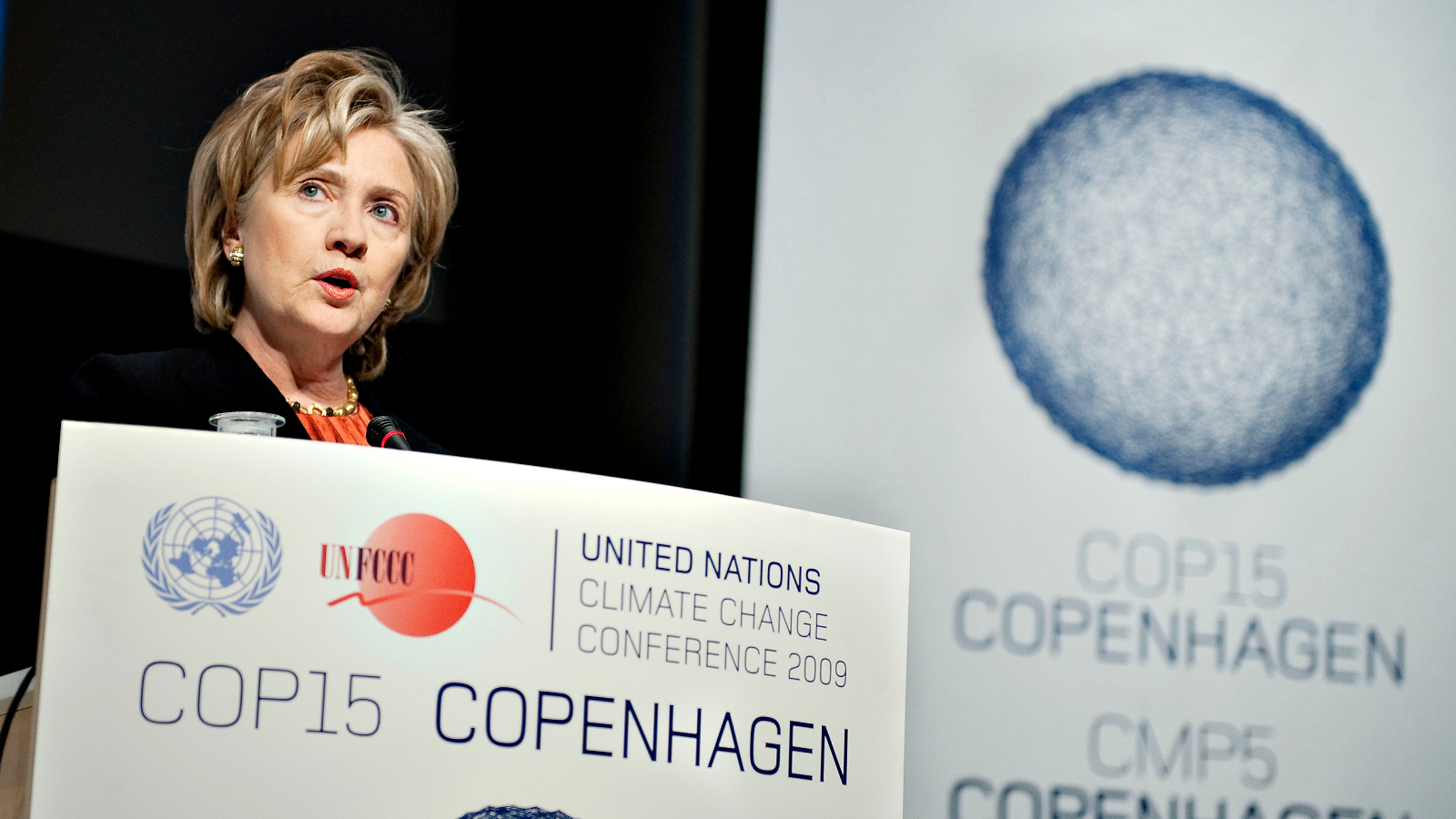

International climate negotiations have been grappling with a broken promise for years. Following the failed negotiations at the 2009 UN climate conference in Copenhagen, wealthy nations, led by the United States, committed to providing $100 billion in climate aid annually to developing countries by 2020. This funding was meant to address the disparities in climate change impacts. However, rich countries missed the target in both 2020 and 2021, leading to strained relations and stalled progress at the annual COP conferences.

A recent report from the OECD reveals that wealthy nations have finally exceeded the $100 billion goal in 2022, albeit two years behind schedule. They contributed close to $116 billion in climate aid to developing countries in 2022, making up for the gaps of the previous two years and instilling some hope for progress.

Climate finance expert Joe Thwaites from the Natural Resources Defense Council commends the efforts to overachieve on the funding commitment, emphasizing the importance of making amends for past shortcomings.

Despite this progress, the $100 billion falls significantly short of the estimated $2.4 trillion needed annually by developing countries to transition from fossil fuels and adapt to climate change by 2030.

Concerns persist regarding the nature and transparency of the current climate funding. The OECD report indicates that a significant portion of the public finance provided in 2022 came in the form of loans, rather than grants. This puts developing countries in debt and raises questions about the effectiveness of the aid.

Negotiations in Bonn, Germany, ahead of COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, will focus on setting a new collective goal for climate aid to developing countries this year. Various proposals have been put forward, with some suggesting $1 trillion annually as a suitable figure. Additionally, there is a push to broaden the contributor base to include relatively wealthy countries classified as “developing.”

The report’s findings could provide leverage to wealthy nations during these negotiations, paving the way for greater accountability and trust-building measures.

The OECD report highlights a growth in funding from multiple sources, including multilateral development banks, the private sector, and public finance from governments, with private-sector funding experiencing a significant increase in 2022.

Specific progress has been made in funding for adaptation measures and disaster-resilient infrastructure, essential components of climate finance often overshadowed by other priorities.

While loans continue to dominate the funding landscape, there is a growing recognition of the need to increase grant-based funding, particularly for non-revenue-generating projects like climate adaptation.

The focus now shifts to ensuring that climate financing mechanisms are aligned with the needs and priorities of developing countries, avoiding debt traps and fostering sustainable climate solutions.

Editor’s note: The Natural Resources Defense Council is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.