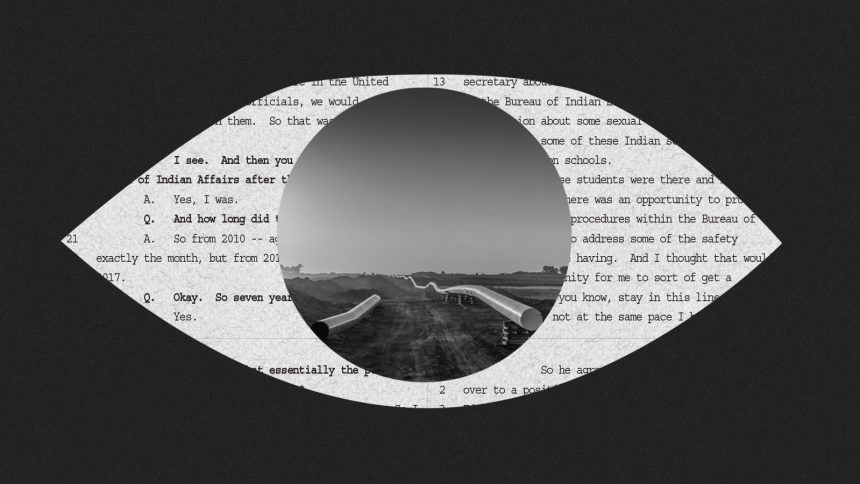

At the height of the mass protests against the Dakota Access pipeline in 2016, the FBI managed up to 10 informants embedded in anti-pipeline resistance camps near the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation. This new information about federal surveillance of an Indigenous environmental movement was revealed during a legal battle between North Dakota and the federal government regarding the costs of policing the pipeline protests. Until now, only one other federal informant in the camps had been confirmed, with reports suggesting that FBI agents in civilian clothing were also sent to the camps.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) operated undercover narcotics officers out of the Prairie Knights Casino on the reservation, where many pipeline opponents were staying. The surveillance strategy included the use of drones, social media monitoring, and radio eavesdropping by various state, local, and federal agencies. This FBI infiltration is part of a broader history of federal agencies monitoring Indigenous movements, dating back to the 1970s when the FBI infiltrated the American Indian Movement (AIM).

The anti-pipeline protests, led by Indigenous people, drew thousands of individuals seeking to protect water, the climate, and Indigenous sovereignty. Participants faced militarized law enforcement and harsh conditions during the seven-month protest. After the completion of the pipeline, North Dakota sued the federal government for over $38 million, citing expenses related to policing, emergency responders, property damage, and environmental harm.

The lawsuit highlighted anti-pipeline camps on federal land managed by the Army Corps of Engineers, which North Dakota claims allowed illegal activities to take place. The federal government’s response to the protests, including the use of informants, drones, and undercover officers, was detailed in depositions of law enforcement officials involved in the protests. The extensive infiltration of the movement by federal agencies showcases the lengths to which they went to monitor and intervene in the protests.

Despite the presence of informants and undercover officers, the FBI did not uncover widespread criminal activity beyond personal drug use and minor offenses. The use of drones by Customs and Border Protection added another layer of surveillance to the protests. Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the pipeline, donated $15 million to North Dakota to help cover policing costs during the protests. The company’s private security contractor, TigerSwan, cooperated with local law enforcement and conducted its own surveillance operations during the protests.

The relationship between federal law enforcement agencies, private security firms, and energy companies underscores the complex dynamics at play during the anti-pipeline protests. The history of infiltration of Indigenous movements by federal agencies raises concerns about the impact on social movements based on kinship networks and community relations.