In a well-known excerpt from his memoir, “Life on the Mississippi,” Mark Twain reflects on how his perspective of the river evolved during his time as a steamboat pilot. Twain describes the river as a “wonderful book,” with bends and eddies that held meaning only for him, not his passengers. However, he laments that the romance and beauty of the river had been lost, as it was now solely viewed as a tool for safely navigating a steamboat.

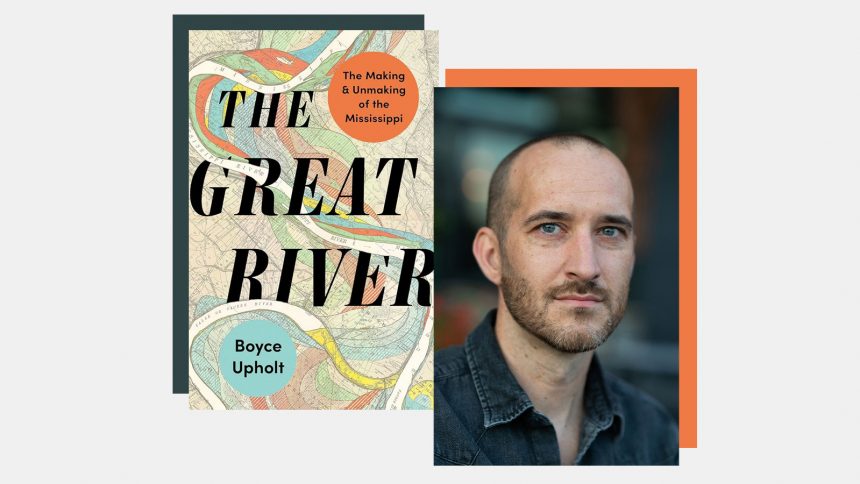

This passage serves as a reminder of how we interact with and discuss the environment. Rivers like the Mississippi are not just sources of beauty but also products of human intervention, manipulated for economic gain. In Boyce Upholt’s captivating book, “The Great River,” he delves into the history of the Mississippi through the lens of those who sought to control it. Upholt reveals the consequences of short-sighted decisions made in the name of progress, shedding light on the impact of colonial hubris.

The book explores how the United States has altered the river’s natural course, illustrating a cautionary tale for coastal cities and other regions. Upholt challenges us to consider not just the fate of the Mississippi in a changing climate, but also what the river’s history teaches us about our relationship with nature. By examining the efforts to control the river, Upholt warns of the dangers of trying to overpower natural forces.

The narrative unfolds through the stories of the Army Corps of Engineers, the agency tasked with managing the Mississippi for nearly two centuries. Upholt highlights the Corps’ ambitious projects to tame the river, often with mixed success. The book showcases the clash between engineers like Eads and Humphreys, revealing the devastating consequences of prioritizing control over nature. Upholt also introduces figures like Fisk, who uncovered the river’s untamed essence through his mapping.

The heart of Upholt’s book lies in the examination of the Old River control system, a stark example of human intervention gone awry. This structure symbolizes the struggle to harness the power of nature, offering a cautionary tale for addressing climate change. Upholt emphasizes the importance of finding harmony with nature, referencing Indigenous earthworks as models of coexistence with the environment.

In conclusion, Upholt’s exploration of the Mississippi River serves as a powerful reminder of the limits of human control. By revisiting the past and respecting the river’s natural rhythms, we may find a way to coexist with and protect our environment for generations to come.